Moving Shadows

Revisiting JXM

In South African Wine on 15 Nov 2013

People who know me personally might be aware of (or, perhaps more accurately, tolerate) the fact that I love the early music of Barenaked Ladies. One of my favorite of their songs, “The Old Apartment,” recounts the experience of coming back to a place you once lived, finding it changed, remembering the good and the bad in every room, and recalling the “broken glass, broke and hungry, broken hearts and broken bones” of those years.

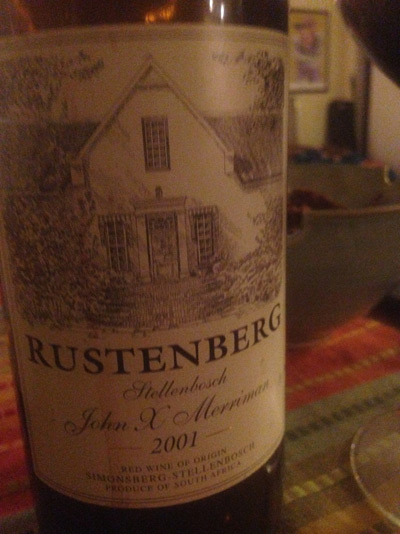

Wine, books, records, and movies are like that for me, in a way; remember in the film High Fidelity (this is going to be a post of pop culture references) when Rob is organizing his record collection autobiographically? Wines are like that for me. And when I see the Rustenberg John X Merriman label in a store or on a website, I don’t see a ridiculous-value $25 Bordeaux blend. I see the strange juxtaposition of savoring the wine in its element, marveling at its intensity and raw perfection, and then the next day selling it to a stockbroker who wanted to impress his boss with a first-growth gift on a Target-card budget. I see four vintages of this wine flash before my eyes at tasting parties, birthdays, dinners, and late nights at home, and I see the Rustenberg farm, a herd of cows against a backdrop of the Simonsberg mountains, and the moment of realization that I could happily drink South African wine every day for the rest of my life.

A good friend gave me this bottle with the caution that he wasn’t sure how it had been stored; I had no idea what I was in for when I opened it last week, but I have to confess that I lack the patience for cellaring wines. A looming awareness––responsible for many of my impulsive life decisions––that a freak accident could end my life tomorrow rears its head whenever someone tells me a bottle “needs a little time”; I’d rather drink it too young than miss out, and I was dying to taste this rare find: a 2001 JXM.

2001 was a hot, dry vintage in South Africa; it’s considered an excellent vintage for red blends, with great structure and aging potential. Adi Badenhorst, now owner of A.A. Badenhorst and one of the founding members of the Swartland Revolution, made this wine during his nine-year tenure at Rustenberg. The blend this vintage consisted of 53 percent merlot, 42 percent cabernet sauvignon, and 5 percent cabernet franc; Badenhorst recommended in his winemakers’ notes that it be aged up to ten years.

What a marvel it must have been a few years ago! Drinking this wine was like wandering into the house of my childhood and discovering a novel in the attic that I’d loved long ago. The familiar traits were there, but I was just a little too late: the sandstone and scorched earth on the nose, the blood and gunfire palate, all melting and curling at the edges like a gallery full of precious artwork slowly engulfing in flames. But I’ve always been something of a pyromaniac.

Of course, there’s an element of sadness in opening an exciting wine just past its prime (perhaps it was less-than-optimally cellared; I’d love to know how this same vintage is holding up sans the variables of overseas transport and retail storage). But it was still a beautiful experience, and unlike memories rekindled or valued treasures rediscovered, this particular wine will continue being made, thank goodness. With fresh awareness of why it remains consistently one of my all-time favorites, I can purchase a bottle of the current vintage, open it when I can’t wait any longer, and make some new memories.